Posted: July 10, 2012 by R.T. Fitch

by Andrew Cohen as it appears in The Atlantic

As Wyoming swelters under the summer heat, as the ash and dust from its forest fires spread out across the Western states, as a sustained drought deepens the fissures in its barren expanses of scrub and rock, the battle over the fate of thousands of its wild horses has just exploded anew in court. Here is a nasty bit of litigation worth watching for many different reasons, not the least of which is that may help more people better understand the magnitude of the economic and political forces which are currently arrayed against the federally-protected American mustang.

As Wyoming swelters under the summer heat, as the ash and dust from its forest fires spread out across the Western states, as a sustained drought deepens the fissures in its barren expanses of scrub and rock, the battle over the fate of thousands of its wild horses has just exploded anew in court. Here is a nasty bit of litigation worth watching for many different reasons, not the least of which is that may help more people better understand the magnitude of the economic and political forces which are currently arrayed against the federally-protected American mustang.

The short version is a familiar one. Area ranchers, who never wanted the horses around to begin with, now want the herds gone completely from a vast “checkerboard” patch of public and private land in southwestern Wyoming, in and around Sweetwater County, near Rock Springs. They allege that the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management has “utterly failed” to limit the number of wild horses which roam these million-acre (or two-million acre) ranges. We have a legal right to declare we want no horses on these land, the ranchers claim, and it’s now time we exercised that right.

Advocates of the wild horses, who have intervened in the case, argue that the ranchers have no such legal right to push the BLM into removing more wild horses than they already have from Wyoming’s public and private lands. These tribunes say that federal officials– led by Interior Secretary Ken Salazar himself, a longtime Colorado rancher– have aggressively reduced Wyoming’s herds, often at great peril to the horses and always at significant expense to taxpayers, who pay for both the roundups and the massive holding facilities where tens of thousands of wild horses now are corralled.

And the feds? As usual, the government is caught betwixt and between. The BLM evidently cannot remove Wyoming’s wild horses fast enough to satisfy the ranchers. And it clearly cannot keep enough of the herds near Sweetwater County to satisfy the horse advocates. Indeed, one of the most disappointing aspects of the flurry of briefs that have been filed in Rock Springs Grazing Association v. Salazar is the faux indignation offered by federal officials in defense of their herd management policies — as if they didn’t know why this lawsuit came about the way it did.

THE PRELUDE

Even the lead-up to the litigation has dark meaning here. The lawsuit seems to have been driven from within. In early 2010, Interior Department Assistant Secretary Sylvia Baca, the former oil company executive, candidly told the ranchers that they would have to sue her own agency to vindicate their claimed right to get rid of the horses. This is the same Sylvia Baca, a BP veteran, whose subsequent work for the Interior Department’s Minerals Management Service has worried environmentalists and others concerned about the oil and gas industry’s influence on the agency required by law to oversee it.

The parties appear to disagree on precisely what Baca said, however, and there even is some room between versions offered by the ranchers. Last year, when the lawsuit first was filed, the Grazing Association wrote in its complaint that Baca, then working for Interior on wild horse issues, “attributed the [BLM's] failure to comply [with horse removal requirements] with external influences on the Department and Congress, and the lack of funding due to the need to contract for sanctuaries. The Assistant Secretary stated that litigation would be necessary to secure additional funding for wild horse gathers.”

In their opening brief, however, the ranchers have toned it down a bit. They write: “The Deputy Assistant Secretary advised RSGA that DOI policies and priorities made it difficult to offer a solution short of litigation.” Whatever the exact words, Baca’s advice to the ranchers represented an appalling lack of neutrality about the Interior Department’s political and legal mission (which is, in part, to avoid encouraging private parties to sue). More than that, it represented an overt act of hostility toward the federal government Baca still serves. Neither the feds nor the horse advocates mentioned it in their briefs.

THE RANCHERS

The lawsuit began last year but it took a while to heat up. At the end of May, the Rock Springs Grazing Association filed a motion asking a federal trial judge to enter an order forcing the BLM to remove all of the horses in the Checkerboard, an interconnecting pattern of public and private land that dates back to the days of the Pacific Railways Act of 1864. Not only is such removal required by federal statute, the ranchers argue, the feds still are bound by the terms of a 1981 federal district court order which had settled an earlier generation of litigation over the area’s wild horses.

The first half of the Grazing Association’s opening brief is interesting, and particularly candid for a court document, because it highlight the two strains of thought and belief that seem to animate the ranchers’ dislike for the wild horses and their human advocates. The anger and frustration the ranchers feel toward the federal government practically shoots itself off the pages. And so does the impression that the ranchers never truly accepted the letter or the spirit of the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971, the Nixon-era federal law that first tried to protect the horses from humans.

The Grazing Association argues that the Wild Horse Act requires federal officials to remove wild horses from private land. Since the ranchers can’t by law build fences separating their land from public land, the Grazing Association says the horses must go for the sake of land conservation. The ranchers contend that because they have reduced grazing of their own livestock” during the current drought it is “outrageous” that the BLM has performed only “token gathers” of wild horses. The tone of the entire brief is contemptuous– and why not? The ranchers seek to hold the feds in civil contempt.

THE FEDS

One month after the ranchers filed their motion, the feds responded. The government’s brief is dry and spare and focuses a great deal upon civil procedure, administrative law and Washington’s version of events surrounding that 1981 court order. Indeed, there is a long history of conflict here between the ranchers and the feds, decades of promises and suspicions, of negotiation and disappointment. All of it is, at least in part, a result of the legislative compromises built into the original statute– as well as new economic forces unleashed by subsequent amendments like this dubious one in 2004.

The feds say that the Wild Horse Act does not require them to remove wild horses from private land any faster than is “practicable” (to use the pragmatically bureaucratic word contained in the Bureau’s own regulations). And they argue that the Grazing Association now is precluded from relying upon the 1981 court order to force the wild horses out any quicker than they already have been forced out by massive roundups In 2011 alone, the feds note in their brief, they removed more than 3,000 wild horses from the five “herd management areas” that are of concern to the Grazing Association.

Here’s how the feds end their opening brief:

The advocates for the wild horses pick up where the feds leave off and come to what clearly is the most politically compelling component to this dispute. It’s not just the order-of-magnitude difference between the small number of wild horses now grazing in the Checkerboard and the huge number of private livestock grazing there. It’s not just about the language of the Wild Horse Act. It’s about a form of social and economic compact the ranchers fail or refuse to recognize. If the Grazing Association wants to play on public land, the horse advocates argue, they should at least pay for it:

In 1982, ranchers were charged $1.82 per AUM (animal unit months, a standard industry measurement). In 1992, the cost was $1.92 per AUM. By 2002, the cost was lowered to $1.42. Today, and since 2007, the cost has been $1.35. This is “the lowest fee that can be charged,” dryly notes the 2012 Congressional Research Service report chronicling these figures. (See below). It’s no wonder that Anadarko, the corporate oil, gas and land giant with major investment in this part of Wyoming, has also entered the litigation as an intervenor. As with every other story involving law and politics, no matter how far away from Washington, the quickest way to figure out what’s going on is to follow the money.

THE RATES

Finally, to illustrate the extent to which the federal government subsidizes ranching, here is a passage from a Congressional Research Service report, dated June 19, 2012, and titled “Grazing Fees: Overview and Issues.”

The BLM evidently cannot remove Wyoming’s wild horses fast enough to satisfy the ranchers

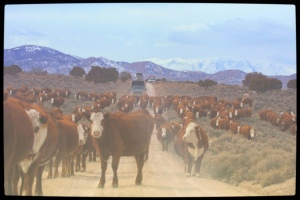

Privately owned welfare cattle being herded into Antelope Complex, Feb 2011, as BLM wild horse roundup is going on at the same time. ~ photo by Terry Fitch

The short version is a familiar one. Area ranchers, who never wanted the horses around to begin with, now want the herds gone completely from a vast “checkerboard” patch of public and private land in southwestern Wyoming, in and around Sweetwater County, near Rock Springs. They allege that the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management has “utterly failed” to limit the number of wild horses which roam these million-acre (or two-million acre) ranges. We have a legal right to declare we want no horses on these land, the ranchers claim, and it’s now time we exercised that right.

Advocates of the wild horses, who have intervened in the case, argue that the ranchers have no such legal right to push the BLM into removing more wild horses than they already have from Wyoming’s public and private lands. These tribunes say that federal officials– led by Interior Secretary Ken Salazar himself, a longtime Colorado rancher– have aggressively reduced Wyoming’s herds, often at great peril to the horses and always at significant expense to taxpayers, who pay for both the roundups and the massive holding facilities where tens of thousands of wild horses now are corralled.

And the feds? As usual, the government is caught betwixt and between. The BLM evidently cannot remove Wyoming’s wild horses fast enough to satisfy the ranchers. And it clearly cannot keep enough of the herds near Sweetwater County to satisfy the horse advocates. Indeed, one of the most disappointing aspects of the flurry of briefs that have been filed in Rock Springs Grazing Association v. Salazar is the faux indignation offered by federal officials in defense of their herd management policies — as if they didn’t know why this lawsuit came about the way it did.

THE PRELUDE

Even the lead-up to the litigation has dark meaning here. The lawsuit seems to have been driven from within. In early 2010, Interior Department Assistant Secretary Sylvia Baca, the former oil company executive, candidly told the ranchers that they would have to sue her own agency to vindicate their claimed right to get rid of the horses. This is the same Sylvia Baca, a BP veteran, whose subsequent work for the Interior Department’s Minerals Management Service has worried environmentalists and others concerned about the oil and gas industry’s influence on the agency required by law to oversee it.

The parties appear to disagree on precisely what Baca said, however, and there even is some room between versions offered by the ranchers. Last year, when the lawsuit first was filed, the Grazing Association wrote in its complaint that Baca, then working for Interior on wild horse issues, “attributed the [BLM's] failure to comply [with horse removal requirements] with external influences on the Department and Congress, and the lack of funding due to the need to contract for sanctuaries. The Assistant Secretary stated that litigation would be necessary to secure additional funding for wild horse gathers.”

In their opening brief, however, the ranchers have toned it down a bit. They write: “The Deputy Assistant Secretary advised RSGA that DOI policies and priorities made it difficult to offer a solution short of litigation.” Whatever the exact words, Baca’s advice to the ranchers represented an appalling lack of neutrality about the Interior Department’s political and legal mission (which is, in part, to avoid encouraging private parties to sue). More than that, it represented an overt act of hostility toward the federal government Baca still serves. Neither the feds nor the horse advocates mentioned it in their briefs.

THE RANCHERS

The lawsuit began last year but it took a while to heat up. At the end of May, the Rock Springs Grazing Association filed a motion asking a federal trial judge to enter an order forcing the BLM to remove all of the horses in the Checkerboard, an interconnecting pattern of public and private land that dates back to the days of the Pacific Railways Act of 1864. Not only is such removal required by federal statute, the ranchers argue, the feds still are bound by the terms of a 1981 federal district court order which had settled an earlier generation of litigation over the area’s wild horses.

The first half of the Grazing Association’s opening brief is interesting, and particularly candid for a court document, because it highlight the two strains of thought and belief that seem to animate the ranchers’ dislike for the wild horses and their human advocates. The anger and frustration the ranchers feel toward the federal government practically shoots itself off the pages. And so does the impression that the ranchers never truly accepted the letter or the spirit of the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971, the Nixon-era federal law that first tried to protect the horses from humans.

The Grazing Association argues that the Wild Horse Act requires federal officials to remove wild horses from private land. Since the ranchers can’t by law build fences separating their land from public land, the Grazing Association says the horses must go for the sake of land conservation. The ranchers contend that because they have reduced grazing of their own livestock” during the current drought it is “outrageous” that the BLM has performed only “token gathers” of wild horses. The tone of the entire brief is contemptuous– and why not? The ranchers seek to hold the feds in civil contempt.

THE FEDS

One month after the ranchers filed their motion, the feds responded. The government’s brief is dry and spare and focuses a great deal upon civil procedure, administrative law and Washington’s version of events surrounding that 1981 court order. Indeed, there is a long history of conflict here between the ranchers and the feds, decades of promises and suspicions, of negotiation and disappointment. All of it is, at least in part, a result of the legislative compromises built into the original statute– as well as new economic forces unleashed by subsequent amendments like this dubious one in 2004.

The feds say that the Wild Horse Act does not require them to remove wild horses from private land any faster than is “practicable” (to use the pragmatically bureaucratic word contained in the Bureau’s own regulations). And they argue that the Grazing Association now is precluded from relying upon the 1981 court order to force the wild horses out any quicker than they already have been forced out by massive roundups In 2011 alone, the feds note in their brief, they removed more than 3,000 wild horses from the five “herd management areas” that are of concern to the Grazing Association.

Here’s how the feds end their opening brief:

For over a century, [Rock Springs Grazing Association] has benefited from utilizing public lands, and before RSGA secured its interest in these lands, wild horses were present. After 30 years of formal management and agreement, RSGA has changed its mind as to whether this unique land pattern [the Checkerboard] can support wild horses and grazing. RSGA is free to change its mind under the Wild Horses Act, but the speed at which BLM complies with the request to remove these horses from RSGA’s land must take into account the prior history and unique land management issues presented on the Checkerboard.THE ADVOCATES

The advocates for the wild horses pick up where the feds leave off and come to what clearly is the most politically compelling component to this dispute. It’s not just the order-of-magnitude difference between the small number of wild horses now grazing in the Checkerboard and the huge number of private livestock grazing there. It’s not just about the language of the Wild Horse Act. It’s about a form of social and economic compact the ranchers fail or refuse to recognize. If the Grazing Association wants to play on public land, the horse advocates argue, they should at least pay for it:

While RGSA is complaining about a hundred extra wild horses on two million acres of land– half of which are publicly owned– RGSA is permitted to have the year-round equivalent of tens of thousands of private livestock grazing on these same lands for its own economic benefit at taxpayer expense enough though, despite RGSA’s statement to the contrary, this livestock is competing for the same forage that is needed by the wild horses that are statutorily required to be protected (emphasis in original).One of the issues worth focusing upon here and now, the advocates say, is the extent to which the private and corporate beneficiaries of “welfare ranching” now seek to further dictate the terms of their sweetheart deals with the federal government. Among other things, “welfare ranching” describes the process by which public grazing rights are given to ranchers at ridiculously low fees, a sort of secret subsidy that reportedly costs the American taxpayer hundreds of millions of dollars each year. Shouldn’t the ranchers have to give something in return for the economic benefit they get from the low fees?

In 1982, ranchers were charged $1.82 per AUM (animal unit months, a standard industry measurement). In 1992, the cost was $1.92 per AUM. By 2002, the cost was lowered to $1.42. Today, and since 2007, the cost has been $1.35. This is “the lowest fee that can be charged,” dryly notes the 2012 Congressional Research Service report chronicling these figures. (See below). It’s no wonder that Anadarko, the corporate oil, gas and land giant with major investment in this part of Wyoming, has also entered the litigation as an intervenor. As with every other story involving law and politics, no matter how far away from Washington, the quickest way to figure out what’s going on is to follow the money.

THE RATES

Finally, to illustrate the extent to which the federal government subsidizes ranching, here is a passage from a Congressional Research Service report, dated June 19, 2012, and titled “Grazing Fees: Overview and Issues.”

The BLM and FS are charging a grazing fee of $1.35 per AUM through February 28, 2013. This is the lowest fee that can be charged. It is generally lower than fees charged for grazing on other federal lands as well as on state and private lands. A 2005 study by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that other federal agencies charged $0.29 to $112.50 per AUM in 2004. While the BLM and FS use a formula to set the grazing fee (see “The Fee Formula” below), most agencies charge a fee based on competitive methods or a market price for forage. Some seek to recover the costs of their grazing programs. …

State and private landowners generally seek market value for grazing; in 2004, state fees ranged from $1.35 to $80 per AUM and private fees ranged from $8 to $23 per AUM. In 2010, state grazing fees continued to show wide variation, ranging from $2.28 per AUM for Arizona to $65-$150 per AUM for Texas. Moreover, some states do not base fees on AUMs, but rather have fees that are variable, are set by auction, are based on acreage of grazing, or are tied to the rate for grazing on private lands. The average monthly lease rate for grazing on private lands in 11 western states in 2011 was $16.80 per head.

BLM and the FS typically spend far more managing their grazing programs than they collect in grazing fees. For example, the GAO determined that in FY2004, the agencies spent about $132.5 million on grazing management, comprised of $58.3 million for the BLM and $74.2 million for the FS. These figures include expenditures for direct costs, such as managing permits, as well as indirect costs, such as personnel. The agencies collected $17.5 million, comprised of $11.8 million in BLM receipts and $5.7 million in FS receipts.

For FY2009, BLM has estimated appropriations for grazing management at $49.3 million, while receipts were $11.9 million. The FS has estimated FY2009 appropriations for grazing management at $72.1 million, with receipts estimated at $5.2 million. Receipts for both agencies have been relatively low in recent years, apparently because western drought has contributed to reduced livestock grazing and the grazing fee was set at the minimum level for 2007-2011.

Other estimates of the cost of livestock grazing on federal lands are much higher. For instance, a 2002 study by the Center for Biological Diversity estimated the federal cost of an array of BLM, FS, and other agency programs that benefit grazing or compensate for impacts of grazing at roughly $500 million annually. Together with the nonfederal cost, the total cost of livestock grazing could be as high as $1 billion annually, according to the study.

Grazing fees have been contentious since their introduction. Generally, livestock producers who use federal lands want to keep fees low. They assert that federal fees are not comparable to fees for leasing private rangelands, because public lands often are less productive; must be shared with other public users; and often lack water, fencing, or other amenities, thereby increasing operating costs. They fear that fee increases may force many small and medium-sized ranchers out of business.

Conservation groups generally assert that low fees contribute to overgrazing and deteriorated range conditions. Critics assert that low fees subsidize ranchers and contribute to budget shortfalls because federal fees are lower than private grazing land lease rates and do not cover the costs of range management. They further contend that, because part of the collected fees is used for range improvements, higher fees could enhance the productive potential and environmental quality of federal rangelands.

Click (HERE) to visit the Atlantic and to Comment

- Wild Horse Groups File Preemptive “Motion for Stay” to Stop Possible Back-Door BLM Roundup (rtfitchauthor.com)

- BLM to Remove Up to 50 Wild Horses Due to Alleged Drought (rtfitchauthor.com)

- Wild Horse Advocates Level Another Legal Blow Against BLM’s Bogus Emergency Gather (rtfitchauthor.com)

- It’s Official: BLM’s Welfare Cattle Program Killing Western Public Lands, Wild Horses Not Guilty (rtfitchauthor.com)

- Total Removal of Historic Colorado Mustang Herd Denied (rtfitchauthor.com)

- BLM Hoodwinks Judge (rtfitchauthor.com)

- Mixed message from Wyoming tourism (ppjg.me)

No comments:

Post a Comment